Security-Analysis-Obfuscator-iOS

This is a quick informal analysis of the Obfuscator-iOS library which allows obfuscation of strings for Objective-C and Swift. It’s probably more of a tutorial than anything else and the methods presented here can be applied to any “security” library like this one. There are much faster ways to break this library but we’re going to be running under the following assumptions to make things difficult (despite their improbability):

-

We can’t attach a debugger to the application.

-

We can’t read application memory.

-

We can’t intercept any network communications.

The Dangers of this Library

Before we jump into the fun stuff let’s take a second to outline why even having this code in your project is a security risk. The first thing I immediately noticed after importing this library was that my project wouldn’t build. This was because I’m following the practice of treating warnings as errors and out of the box this library produces warnings. While the code which was generating this warning didn’t necessarily introduce any new attack vectors, it did force me to disable this protection. allowing the project to build regardless of whether it contains warnings or not.

Second, just having a library like this in your project means it can be automically detected which sets off red flags for me. Let’s imagine for a second that you’re a burglar walking down a neighbourhood block looking for a target. You pass five identical houses and then you see one with security cameras, a “beware of dog” sign, and some sort of security system on the front door. Which house do you think has something valuable worth stealing? Maybe you would avoid the extra trouble of the house. How would your behaviour change if you were able to see that security cameras were fake, there was no dog or functioning security system?

Back to application security, attackers are lucky because they automate the process of finding vulnerabilities in a target, and so also vulnerable targets. An attacker would just need to download the entire “block” of apps and run a quick analysis script to find a good target:

- Check for libraries such as Obfuscator using something like ClassDump and grep

- Check for methods which contain keywords such as “key”, “password”, “token”, etc and the run the strings command with a regular expression to see if no strings are exposed which match common patterns for these types of strings

- Check for libraries like parse which require a token to be passed, and then check to see if the tokens are are extractable or hidden by using the method above.

Step 1 will reveal the best targets - apps which have data they believe to be sensitive and poor security practices. Step 2 and 3 can be defeated with the correct usage of security through obscurity. We can insert red herrings which mimic API keys so it won’t look like anything is being hidden unless manual analysis is done.

The biggest danger with this library is the false promises and misinformation it spreads:

Secure your app by obfuscating all the hard-coded security-sensitive strings.

No. You’re not securing anything by doing this. You’re creating a false sense of security and making it easier for attackers to take advantage of your sensitive data.

This makes it harder for people with jail-broken iPhones from opening up your app’s executable file and then looking for strings embedded in the binary that may appear ‘interesting’.

IPAs can be downloaded online without the need of a jailbroken device. Up to iOS 8 you can transfer apps directly to your machine without the need of a jailbreak. Finally, you don’t need to “open up” any binaries to find the strings - check man page for the strings command.

Getting Our Hands Dirty

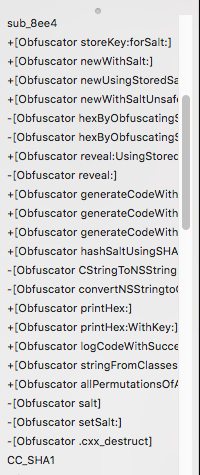

So to get started I’m going to fire up my favorite disassembler Hopper and load in the binary using the pre-selected options. For the sake of this example we can say the app was specifically targeted and no-automated analysis was performed. The first thing I notice when browsing the labels is the name of the obfuscation library:

Seeing that I know immediately that there is sensitive data present and which library is being used to manage it. From there I look up the documentation and find the obfuscation method reveal: which I then search for to find where the procedure where this code is being implemented:

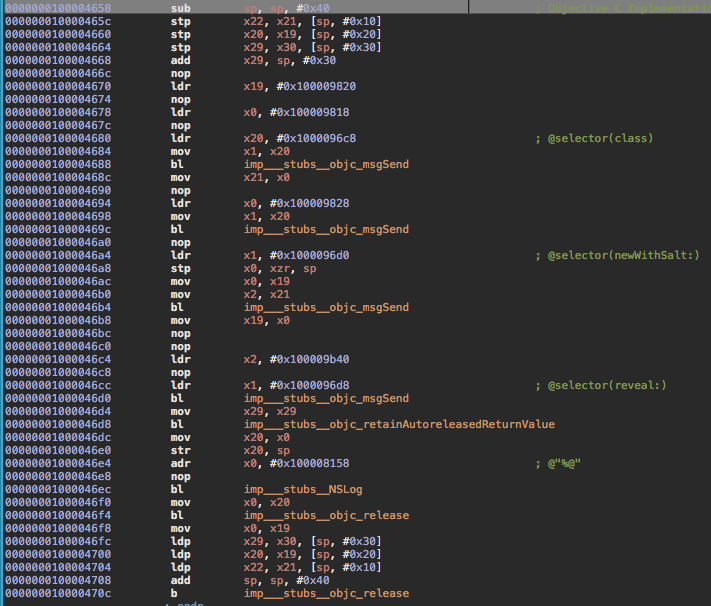

The first thing I notice is the following line:

00000001000046a4 ****ldr**** x1, #0x1000096d0 ; @selector(newWithSalt:)

This tells me a salt is being generated, and so looking at the preceding instructions I’ll be able to determine what is being passed as an argument:

I display the values in the following lines as addresses:

0000000100004678 ****ldr**** x0, #objc_cls_ref_AppDelegate

0000000100004694 ****ldr**** x0, #objc_cls_ref_NSString

Alternatively converting the entire procedure back into code would show the same information without any extra steps.

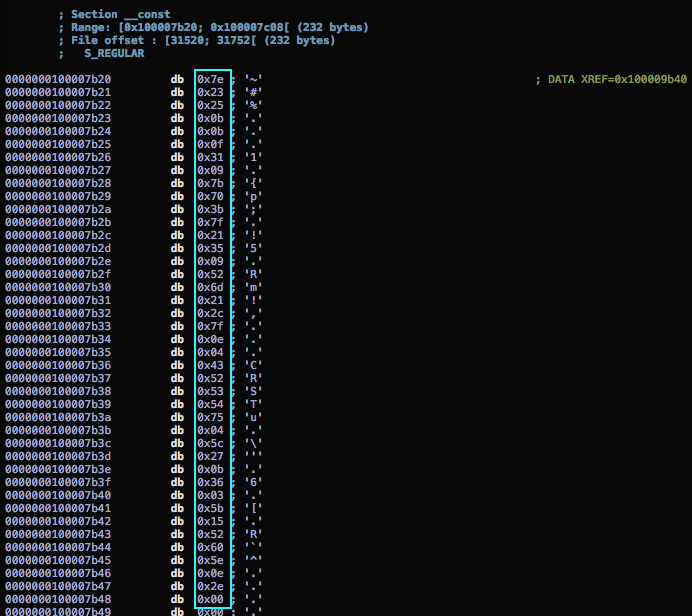

Next I get the obfuscated string itself, the library documentation tells us it will be a a constant char array which looks like this:

const unsigned char _key[] = { 0x11, 0x22, 0x33, ... };

This can be found in the binary by checking the __const section or just finding references to the 0x100009b40 offset in one of the instructions we see before reveal: is called:

So now I have the obfuscated string data and the salt which is enough to obtain the original string. The next step is to write a very basic Objective C application (easier to match the language of the library), which will de-obfuscate and verify the accuracy of the result:

// The library will just use the class name for hashing so we'll follow KISS here

@interface AppDelegate : NSObject

@end

@implementation AppDelegate : NSObject

@end

// The DEBUG flag has to be set to test obfusaction

#define DEBUG 1

// < The Obfuscator code from the library goes here >

// And now we build our deobfuscation class

@interface DeObfuscator : NSObject

+ (void)decodeTheStringThenTest;

@end

@implementation DeObfuscator

// This is the array which was obtained from the __const section earlier

const unsigned char found_key[] = {

0x7E, 0x23, 0x25, 0xB, 0xB, 0xF, 0x31, 0x9, 0x7B, 0x70, 0x3B, 0x7F,

0x21, 0x35, 0x9, 0x52, 0x6D, 0x21, 0x2C, 0x7F, 0xE, 0x4, 0x43, 0x52,

0x53, 0x54, 0x75, 0x4, 0x5C, 0x27, 0xB, 0x36, 0x3, 0x5B, 0x15, 0x52,

0x60, 0x5E, 0xE, 0x2E, 0x00 };

// Here we deobfuscate the string and obfuscate it again to ensure accuracy

+ (void)decodeTheStringThenTest {

Obfuscator *o = [Obfuscator newWithSalt:[AppDelegate class], [NSString class], nil];

NSString *str = [o reveal:found_key];

NSLog(@"The de-obfuscated string is: %@", str);

NSLog(@"The re-obfuscated string: %@", [Obfuscator printHex:[o hexByObfuscatingString:str silence:YES]]);

}

@end

//And we setup our main()

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

@autoreleasepool {

[DeObfuscator decodeTheStringThenTest];

}

}

Running this will will output the following, verifying we have indeed defeated this security control:

The ‘secure’ string is: JEG3i8R9LAXIDW0kXGHGjauak0G2mAjPacv1QfkO

The obfuscared result: const unsigned char _key[] = { 0x7E, 0x23, 0x25, 0xB, 0xB, 0xF, 0x31, 0x9, 0x7B, 0x70, 0x3B, 0x7F, 0x21, 0x35, 0x9, 0x52, 0x6D, 0x21, 0x2C, 0x7F, 0xE, 0x4, 0x43, 0x52, 0x53, 0x54, 0x75, 0x4, 0x5C, 0x27, 0xB, 0x36, 0x3, 0x5B, 0x15, 0x52, 0x60, 0x5E, 0xE, 0x2E, 0x00 };

Conclusion & AppSec Practices

So as we saw this library does nothing more than paint an application as a target, the strings can be de-obfuscated with little difficullty or knowlege. The steps I outlined above are far from advanced techniques and anyone who has fifteen minutes to spare would be able to read a tutorial similar to the above and defeat this “security” control.

There are some basic principles for developing secure applications which I think all developers should follow. This may be opinionated, but they’re concepts I’ve taken from OWASP, IBM, and 14 years of reversing/securing applications:

- Always use the lowest-level APIs possible when working on security-related code

- When dealing with sensitive data manage memory yourself

- Don’t rely on 3rd party frameworks to secure your application (especially those which are no longer maintained)

- Security through obscurity is not security at all - it’s a valid security layer only when layered on top of good security.

Research and think for yourself, don’t widen the attack surface of an application because of five paragraphs on Medium or LinkedIn written by someone looking to market themselves while possessing little if any professional security knowledge. If you use Stack Overflow also be aware that it’s users are notorious for instinctively regurgitating outdated/opinionated answers regarding security.

The code used in this article is available here.