Securing Strings in iOS Apps

Many applications rely on strings which contain potentially sensitive data for storing things such as URIs, tokens, keys and secrets. Many of these items are required for core app functionality and must be hardcoded in the source, they can be used as arguments for functions or stored as constants when re-used. Although hidden from the typical user, we can never make the assumption that these strings are safe.

The ‘strings’ command

Strings looks for ASCII strings in a binary file or standard input. Strings is useful for identifying random object files and many other things. A string is any sequence of 4 (the default) or more printing characters [ending at, but not including, any other character or EOF]. Unless the - flag is given, strings looks in all sections of the object files except the

__TEXTsection.

String extraction from binaries is pretty straightforward thanks to this command. All an attacker needs to do is point it towards an application’s unencrypted binary (which is easily obtained from a jailbroken device) and every string in the binary will be dumped to a list. I put together a very quick test application to analyz, inside there are four variations of a basic API client class which uses an API key:

NinjaClient- “APIKey1” (custom solution - discussed below)CPPClient- “APIKey2” (C++)ObjCClient- “APIKey3” (Objective-C)SwiftClient- “APIKey4” (Swift)

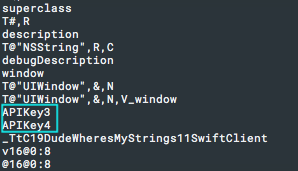

And here is a portion of the output from running strings:

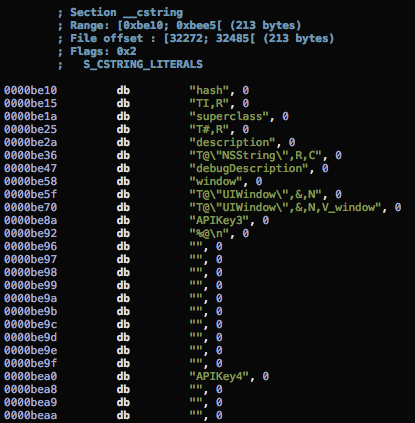

If you take look at the binary itself you’ll see this data is coming from the __cstring section:

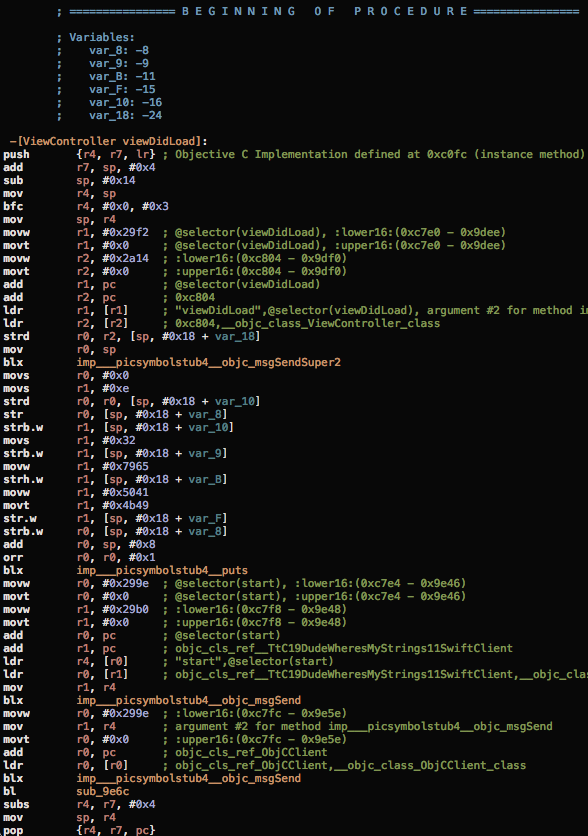

As you can see above the strings in the last two classes are clearly visible. The string in the C++ remains hidden, in order to find it we would need to use a disassembler or hex editor. All four methods are called in the viewDidLoad function so it’s easy to find a starting point:

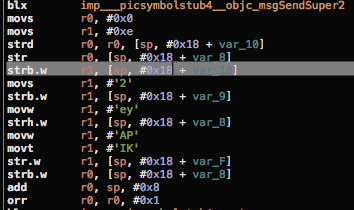

From there it’s not immediately clear where the string is but you will notice some unusually high hex values after the first blx instruction. Getting the string representation of these values reveals the string (though out of order):

Securing Strings

So how do you secure the strings in your application? Some articles I’ve read point towards using libraries such as Obfuscator, but this is involves multiple non-fun steps for a developer to implement and leaves the code full of comments storing the original strings. Not to mention that this library also does little more than announce to the world you’re trying to hide something, the hashing method it uses can be defeated in a few minutes.

The solution I propose accomplishes the following:

- Removes the string from the strings table and prevents it from easy discovery in hex editors

- Stores it in the code in a way which is easy to read and write

- Does not easily reveal the string in a disassembler.

- Comes in under 20 lines with include statements.

- Does not require any code generation through scripts or the binary itself.

The original idea came from StackOverflow and the logic is dead simple:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string>

#include <cstring>

class Xtring: public std::string

{

public:

Xtring(std::string str)

{

std::string phrase(str.c_str(), str.length());

this->assign(phrase);

}

Xtring c(char c) {

std::string phrase(this->c_str(), this->length());

phrase += c;

this->assign(phrase);

return *this;

}

};

//Usage:

Xtring str("");

std::string keyString = str.c('A').c('P').c('I').c('K').c('e').c('y').c('1');

The assembly for the above example is too long to include in this post but you can view it as a gist here.

It is still possible to extract the string, but now it’s split up by individual characters and spaced apart in the instructions. This makes it much more time consuming to attempt to decipher.

This solution definitely isn’t the most advanced, but that’s the point. What it does is provide a simple way to quickly prevent a string from being easily discovered through a hex editor, disassembler, or just the strings command. It does this without revealing itself, drawing much attention or adding unnecessary overhead. In most scenarios this is enough protection. If an attacker is able to get far enough to defeat this mechanism they will also have the knowledge (thanks to the disassembler) to obtain the string through other means such as MITM, a debugger or a memory editor.

The code used in this project is available here.